14 October 2007

Endangered Species 5K

Yesterday I ran my second-ever competitive race, the Endangered Species Walk/Run 5K, described thusly: "co-hosted by the Department of Conservation, the Department of Natural Resources, the Department of Health and Senior Services, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Jefferson City Parks, Recreation, and Forestry Department. The event raises funds to help restore habitat, conduct research and support education projects for endangered animals and plants in Missouri."

I've always been more of a meditative runner than a competitive one; for me, there's nothing better than a long, empty trail under a brooding sky with an intriguing mix on my MP3 player, and no one else in sight. Racing was fun when I was a kid--I was pretty darn good at the 50-yard dash back in the day--but has never interested me since. But once in a while I suffer from the temporary insanity of wanting to do it, maybe as a barometer of whether I'm as healthy as I think I am. The availability of an event nearby that benefitted something important to me made it the right choice.

It turned out to be a great time, and despite the lack of any focused training on my part (I'd been running a couple days a week and biking 3 or more days a week over the last few months), went like clockwork, almost surprisingly so. I think it was a combination of just enough good choices leading up to and during the race:

- I typically run on the Hinkson trail, which has no distance markers--which is good for a distraction-free run, but bad for having any idea how well I'm running, speed-wise. Earlier this week I did an extra run back on my old stomping grounds of the MKT trail, and timed my miles in a simulated 5K. My first mile was terrible--I was dragging badly--my second mile was great, and my third was somewhere in between. This run gave me something to beat and told me where my biggest weakness was: in the early stages.

- Made an effort to eat nutritionally and heartily and get good nights' sleep in the few days before the race. Mixed success, but good overall.

- I hardly ever drink coffee, but I decided to follow some advice I read on Runnersworld.com to drink a bit of coffee 30-60 minutes before a race, based on the idea that caffeine prepares the nervous system for exercise.

- I asked Ann Marie, herself a cross-country star in high school, what her pre-race prep was in her racing days. She emphasized a long warm-up, even to the extent of running the whole race course before the real race. While I didn't think I was up for quite that much, her advice made immediate sense with what I had experienced just a few days earlier--hitting a wall in my first mile that mentally dragged me down for the rest of the run. So when we got to the race site, in addition to my usual alternating 1-minute-jog/1-minute-walk warmup repeats, I ran a good six minutes non-stop at just below race pace. During that run I hit that draggy, breathing-hard wall, but did not hit it during the actual race, so this turned out to be critical and I'm now sold on the longer-warmup approach.

- I ended up being in a surprisingly good, practical frame of mind during the race itself. I'd thought through a few things ahead of time to avoid getting surprised, and switched between multiple mindsets throughout the race: checking in on myself to make sure I was at a comfortable pace, and then bumping it up a notch; looking around at the lovely morning sky and countryside; thinking about things I'm working on outside of the race; checking out the cute girl in front of me and then passing her (hey, motivation is motivation); and even zoning out altogether at a few points. The first mindset, which I kept coming back to regularly, was the most important; I think I underestimated myself a little early on, and was able to steadily increase my pace through the race, ending with the last 100 meters or so in a sprint.

See a few photos documenting my race-day experience.

Labels: Environment, Life, Running

29 July 2007

Phosphorus: The living end?

Hovering in the back of my mind for some time now has been a quietly monumental idea that I read in Isaac Asimov's 1962 book Fact And Fancy. In the book's first essay, "Life's Bottleneck", Asimov lays out an astounding but logical notion: that the ultimate limiting factor for the amount of life on Earth is phosphorus, and that our supply is rapidly diminishing, thus constantly lowering the ceiling on the amount of life that the world can sustain.

In a nutshell, phosphorus is one of the most critical elements in the biological building blocks and processes in all life, and the amount required for plant & animal life to exist vs. the concentration of usable phosphorus in water and soil is the limiting factor in life's development on earth.

The issue that we face is the availability of that usable phosphorus. Asimov explains that, in effect, the world's phosphorus is steadily falling down to the bottom of the sea, where it is no longer usable and is not being recovered at a rate to balance out its loss.

The reason for this is that the movement of phosphorus is largely one-way. Asimov explains the example of phosphorus in soil:

The rain comes down, dissolves tiny quantities of soil, and on this solution, plants grow until all the phosphorus they can grab has been incorporated into their substance. Animals eat the plants and, in the process of living, excrete phosphorus-containing wastes upon which plant life can feed, grow, and replace the amount of itself which animals have eaten...

And just as there is a drizzle out of the euphotic zone of the ocean, so there is a drizzle out of the land. Some of the dissolved materials in the soil inevitably escape the waiting rootlets and are carried by the seeping soil water to brooks and rivers and eventually to the sea.

That might not sound like a dramatic process, but Asimov continues:

...it is estimated that 3,500,000 tons of phosphorus are washed from the land into the sea by the rivers each year. Since phosphorus makes up roughly 1 per cent of living matter, that means that the potential maximum amount of land-based protoplasm decreases each year by 350,000,000 tons.

Phosphorus is steadily being transferred from land to sea (through transmission into rivers, which in turn carry it to the sea), and from the upper parts of the ocean to the ocean floor. Once it reaches the ocean floor, which is already saturated with more phosphorus than can be used by the life present at that depth, it is essentially out of the reach of land-based life.

A point made by Asimov, and again this past week on the Treehugger web site, is that humans are literally flushing away vast amounts of phosphorus every day, through our modern plumbing and sewage systems. In the quote above, Asimov points out the natural flow of phosphorus from the soil through plant life to animal life and back to the soil. But our modern sewage systems take the phosphorus present in our own waste matter and send it directly into the sea--in essence, pouring our world's capacity for life on land literally down the drain.

What must be done about this and what can be done about this is a topic for another time (and some suggestions are noted in the previous paragraph's link). But the gravity of this idea is worth pondering--what other fundamental aspects of life on Earth are we affecting, completely unawares, through simple scale and seemingly unconnected behaviors?

Labels: Environment

01 April 2007

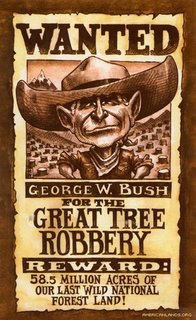

Bush blocked on weaker forest rules

Good news for our national forests: this past Friday a federal judge threw out new rules enacted by the Bush administration that would have allowed commercial use of forests without lengthy environmental reviews.

Good news for our national forests: this past Friday a federal judge threw out new rules enacted by the Bush administration that would have allowed commercial use of forests without lengthy environmental reviews.According to this story, "when government officials announced in December 2004 the first new rules since the 1970s, they said changes would allow forest managers to respond more quickly to wildfires and other threats such as invasive species."

But this looks like little more than a smoke screen for what amounts to a federal subsidy for logging and mining industries--in other words, corporate welfare for industries which are rapidly burning through their supply of private lands to use as fuel. This is only one example of such corporate welfare, used to prop up inherently unsustainable industries for the sake of an artificial standard of economic growth.

With real agriculture and manufacturing capacity on a long and steady decline in this country, we're trading an economic focus on industries that could keep us competitive in the international arena for short-sighted, destructive, polluting industries like coal, timber, and oil, which will only drain our resources, pollute our ecology, and turn us further into consumers--rather than producers--than we already are. Add this to our already astounding trade deficits, and it doesn't paint a pretty picture for the economic future.

As I see it, this attempt at a rule change by the Bush administration is also part of a larger effort to turn over our public resources to private interests. Bush has drastically cut funding for our national land management, requiring huge cuts in national park budgets and staffing, and forcing our national lands to rely more on private oversight, with the expected disastrous results.

This ideological distortion of the purpose and protection of our public lands shames me as a citizen and someone who cares about the natural world, and it makes me further ashamed of the President. But if you're in favor of government-approved books that claim the Grand Canyon is 6,000 years old and was created by Noah's flood, then maybe this all makes sense somehow.

For more on the state of our public forest lands, efforts by the Bush administration to undermine their protection, and citizen efforts to defend them, see the American Lands Alliance. (Note: the image above is from an ALA mailer I received a while back.)

Labels: Environment, Politics

31 March 2007

It's green, but is it good?

A recent issue of Fast Company magazine featured its annual "Fast 50" leaders in business innovation, and this year's focus was on concepts and products that address environmental, social, and health issues around the world--in other words, "green" business ideas that show concern for the world rather than obliviousness to it.

At first, I was really impressed with what they chose to highlight--there area lot of great innovations going on out there, including biodegradable plastic that comes from plant cellulose, the ingenious concepts used by Polyface Farms, peer-networking systems that work around government-imposed Internet censorship (as in China), reemerging electric car technology, some great ideas for cleaner energy sources.

But as I read and considered further, along with all the great ideas for replacing wasteful or toxic technology and practices with healthier substitutes, there was an unsettling thread running through many of the other featured items. The best way I can describe it is a type of business approach that addresses serious problems by adding something to them rather than by trying to truly solve them.

A few examples might explain this best. One featured item involved GAIN, a global partnership between social organizations, the UN, and big agriculture corporations. Their goal is to improve the nutrition of the poor around the world. An extremely important issue, no doubt. But the example the magazine chose to highlight was NutriSip, a nutrition-fortified drink that's distributed in juice-box-style plastic bags to Nigerian schoolchildren. It's even made with local ingredients, so how could that be troubling?

Well, call me picky, but it just seems wrong somehow that the children of Nigeria, with nutritious local food ingredients already available, will become reliant on a Swedish company to provide their nutrition for them, in a plastic-packaged liquid form. Children plagued by poverty are in dire need of nutrition, but "solutions" like this not only trade empowerment for reliance on outsiders, but base their very business model on a lack of self-sufficiency in the customers. If the Nigerian people become more self-sufficient and develop better ways to feed themselves, it will hurt this business venture. Never good to have capitalism blocking your way. It seems to me that it would be better for Nigeria if entrepreneurs found ways to help the people develop their own nutritionally-balanced food production that keeps everything local and removes reliance on outside manufacturing, packaging, and distribution. But where's the money in that?

Another featured item was GE's Water division and its new water-filtering technologies. GE is in the midst of acquiring many new water-purification companies and products, one of which is ZeeWeed, which is "powerful enough to transform Singapore's raw sewage into clean water". Brilliant, from a technological standpoint. What's troubling, though, is that same concept of adding something to a problem instead of truly solving its root cause. The immediate problem, of course, is that there's too much dirty water and not enough clean water. The approach taken here is, "how can we make the dirty water clean?" What seems to be ignored in the process is what seems to me the better question: "how can we prevent the water from getting dirty in the first place?"

Again, it might sound curmudgeonly, but this is troubling to me. We have a situation where industry and overpopulation are creating a massive problem of water pollution and scarcity. Clean water is perhaps the most essential and precious substance on earth (try living off diamonds, baby), and it's under the greatest threat it's ever been. But rather than looking for ways to protect it in the first place, GE's basing a massive corporate venture on ways to profit from polluted water. In other words, its business model relies on the existence of polluted, unusable water.

Now, so long as there are people, there will be polluted water. It's impossible to escape that altogether. But this scenario depends on the continuation of unsustainable polluting behavior by masses of people. Corporate success isn't about mere profit--it's about continuously growing profits, reaching greater and greater heights every quarter, forever. Because of that, only huge-scale pollution will sustain this huge-scale venture. And anything that reduces pollution works against the success of GE.

Think about that. Reducing pollution will weaken GE's business.

It's situations like that which should make us all tremble at the Frankensteinian implications or large-scale capitalism.

Do we really want to rely on distant corporations for our nutrition? Do we really want to rely on massive corporate juggernauts like GE for the most basic elements of life? Almost everywhere in the world, the ingredients for healthy, nutritious, clean, sustaining lifestyles are readily at hand. Corporate control of these resources has created a market where there doesn't need to be a market, and has created need where there doesn't have to be need. This has worked to distance all of us from our own self-sufficiency and virtually obliterated the practice of community self-sufficiency in the developed world.

A great example of a more positive direction is the much-heralded zeer pot, invented by Nigerian professor Muhammed Bah Abba. This simple, ingenious device nests one earthenware pot inside another, separated by an insulating layer of wet sand. It's simple, clean to make, uses readily available ingredients, and can be made, sold, and used locally, without reliance on any outsiders. The results not only improve health, through increased shelf-life for vegetables, but have cultural and local-economic benefits as well:

Traders use desert coolers in the weekly Dutse market which attracts 100,000 people. Farmers and their wives store vegetables in the coolers at home and sell from there or at the market at a good price, instead of sending out their daughters to hawk them at a poor one. This means the girls can go to school, while young men can earn a living in the village instead of going off to Kano. "Aubergines," says Muhammed Bah Abba, "can last for 21 days." Without a desert cooler, they last only a day and a half.

One of his aims is to improve the situation of married women who, traditionally, cannot leave their village. He runs education centres for them and has found that his desert coolers help them earn the money to buy soap and other things they need. They make soft drinks called kunu, zobo and lamurje and sell them from the coolers. They trade in fruit and vegetables, either grown by their husbands or bought from other farmers.

To me, this is real innovation. Something that integrates into and preserves existing cultures, improves quality of life, and creates economic opportunities that produce secondary benefits rather than more waste and pollution.

There's green, and then there's greed. While the new wave of concerned corporate ventures will produce many wonderful things, we must be careful that we don't lose more of our humanity in the process, and must keep "voting with our money" in the best ways we can.

Labels: Culture, Environment, Life

14 January 2007

Why we need electric cars--now!

The story of the electric car is a long and tortured one, which I won't go into here, but it's worth learning about. Here's a teaser from the link above: "most popular roadworthy battery electric vehicles (BEVs) have been withdrawn from the market and have been destroyed by their manufacturers. The major US automobile manufacturers have been accused of deliberately sabotaging their electric vehicle production efforts. Oil companies have used patent protection to keep modern battery technology from use in BEVs."

If that doesn't pique your interest, nothing will. (And it would surprise me, as most of the people who I know have read this blog are the type to be concerned about such things.)

Anyway, it occurred to me in simplest terms today why we positively, urgently need to have electric cars available to us right now: because it would give us true energy independence.

Now, wait a minute, you might say. Electric cars still require lots of energy. We still have to generate all that electricity, and most of our supply comes from environmentally nasty things like coal, which is devastating to mine and poisonous to burn. That's true, and an ugly choice to have to initially make.

But what sets electricity apart from gasoline is that there are lots of ways to get it. If we keep driving gas-powered cars, even gas hybrids, we're still dependent on one unique fuel. We're still handcuffed to petroleum. It's the bottleneck on so many of our cultural advances. It ties us down economically, and it also keeps us tied uncomfortably close to Middle East politics and power struggles. Without our current great dependence on oil, we'd have had so much less contact with and involvement in the Arab world, and it's not a stretch to say that things like 9/11/01 could have been prevented, and certainly our current war too. Most likely, the Middle East would also be happier for our reduced meddling.

With electricity, we would control how it's produced. Coal would generate most of it at first, but all manner of alternative energies will grow and take on more of the load. Wind, water, solar--all of these things have been proven to be sufficient to keep electric cars charged. The result, whether with dirty coal or clean fuels, would be that our country would be independent in the area of our single biggest energy consumption. We'd be able to manufacture both our own cars and our own power. Oil consumption would drop steeply, and we'd be much less beholden to Saudi Arabia and OPEC. The powers in our own government with destructive ties to Big Oil--like the Bush family--would have less influence and less ability to get us into conflicts like our current quagmire.

Don't be fooled by counter-arguments--whatever limitations these cars might have, the opportunities they'd create for us would be immensely greater. The technology is out there right now, and has been for years. Toyota's electric RAV4 dates back to 1997 and the cost to run it was equivalent to getting mileage of 165 miles per gallon.

At the end of the day, we should have the choice. Behind-the-scenes forces in the oil and auto industries have made the choice for us, withholding this technology artificially and against the demand in the free market. Our current type of consumption is getting us into danger, involving us in wars, eating away at our paychecks, and leaving us beholden to foreign interests. In one easy fell swoop, we could turn the tables.

If you agree and want to share that opinion with the auto companies, here are direct links to contact information for some big ones:

Ford

Toyota

GM

Honda

Subaru

Labels: Culture, Environment

18 November 2006

No paving our trails

Earlier this week, a Columbia city panel scuttled the idea of paving our city's recreational trails with asphalt as part of an effort to encourage more trail use and less car use for commuting. The idea, originally proposed by trails consultant Ted Curtis and pushed by the mayor, was met with an enormous wave of opposition from users of the trails. Faced with such opposition, the PedNet panel decided to scrap the idea for existing trails, favoring instead the idea of covering any new city trails with a hard surface, which seems to me like a great compromise. (PedNet has more info on the pros and cons of paved trails.)

After this decision, Curtis said, "I’m a little concerned people are going to focus on [paving the existing trails] and not look at the big picture" of encouraging non-motorized transportation. As it happens, that's precisely the concern many people had about Curtis--that, in focusing on an unwanted change to existing trails, he was missing the bigger picture that Columbia is not a pedestrian-friendly town.

My issue with the original plan was twofold. For the most part, our city's recreational trails aren't very practical for commuters. The MKT trail does connect some significant parts of the city, but the areas it runs through are largely among the parts of town already most friendly to pedestrians. And the city's other recreational trails are pretty inefficient routes to anywhere--much better suited to their intended purpose of recreation than as effective routes of mass commuting.

The real issue when it comes to having a pedestrian- and bike-friendly town has nothing to do with these trails. It has to do with the isolated, inconsistent way that development has taken shape in this town. The size of this town is very manageable--it should be very simple to make this a town that can be easily commuted around without a car. But careless developers and a city council with little interest in cohesive planning have left us with a disjointed, patchwork infrastructure that has been slapped together with little regard for its overall flow. The result is a group of residential islands connected by major roads that are completely unsuited to non-automobile traffic. Our main arteries and all of our major commercial developments are built around the car, plain and simple.

This is why the paved-trail plan falls so far short from a practical standpoint. The vast majority of people in this town would gain no commuter benefit from our current trails. Take me, for example--I live in an old, established neighborhood and work for one of the city's major employers. I work only 5 miles from where I live, but I couldn't take a trail to work even if I wanted to--the routes wouldn't be useful for me. For me to get to work without a car, I'd have to navigate through at least 7 major intersections and travel almost the entire route on multi-lane, dense traffic arteries with no bike lanes (and sometimes no sidewalks or shoulders), 40-50 mph traffic, and major hills. Is it possible to do this? Sure. But is such a prospect going to encourage even 1% of the population to try it? Not a chance.

The key will be new trails and pedways. A significant road-extension project will be starting soon next to my workplace, and it will include an 8-foot-wide pedway running alongside the new road, separated from the main road by a swath of green space. Imagine if all of our city's major roads had such a feature! In a town this size, it would make walking or biking around town a snap. That's the future that PedNet imagines, and it's a great one.

I'll end with the second part of the reason I was opposed to paving our existing trails. As anyone who's read much of my writing on this site knows, I have a deep love for the recreational trails in this city. They provide ready access to a great degree of beauty--flora, fauna, creeks, forests, plains, wetlands. They provide oases of peace and contemplation in a town that's becoming increasingly muddled otherwise. They're a place anyone can go for a walk or bike ride, walk their dog, share the beauty of nature with their kids, play in the streams, even bow-hunt or fish in certain areas.

The gravel & dirt surface of the trails integrates with the natural surroundings. Bugs dig and slither through it, birds forage on it, grass grows in patches of it, water runs cleanly through it, its forgivingly soft surface rolls and ripples with the natural irregularity of the land around it. In short, it has an established identity, a specific beauty that is beloved by me and many others. Most of the people on these trails go there to get away from what is elsewhere, to be in this specific place. That place doesn't need to be turned into a road, with black ooze sealing off and suffocating a swath which would otherwise breathe and live. We don't need asphalt runoff, yellow stripes of paint, and slippery, slowly crumbling black junk carving up these sacred places.

Let them create new trails with all the modern advantages. But in this time when it seems like so much of the natural beauty of this town is being cut down, bulldozed, and paved over, leave us the things that we already have, that we value so much. Let us treasure what we have and make something new to complement it.

Labels: Culture, Environment, Life

07 September 2006

Update: Forest sale plan is dead

An update to an earlier post I wrote back in the spring, about a damn-fool plan by the Bush administration to sell off national forest land to help fund rural schools:

I'm happy to say that it looks like the plan is officially dead, and there's little likelihood of it coming back. With opposition from everyone from the usual environmental groups to the NRA, this and other similar plans have run into broad opposition which reveals just how many people can agree on one thing, at least: we love our public lands.

Aside from the issues of a gross abuse of power and failure to responsibly steward our public land, this topic made me think more about how obsessed this country seems to be with private ownership and hoarding of property and wealth.

If you're interested in the topic of land ownership, the rights of landowners vs. the public good and ecological health, I highly recommend an article in the March/April 2005 issue of Orion magazine, "The Culture of Owning", by Eric Freyfogle. A quote:

Encouraged by federal payment programs, farmers increasingly expect money whenever conservation measures reduce their crop yields. When development would harm a particular landscape, the growing practice is to avert it by buying up "development rights" or purchasing a conservation easement. And rather than banning landowners from destroying critical wildlife habitat (a ban that's quite legal under the federal Endangered Species Act), the Fish and Wildlife Service is now prone to pay them to leave the habitat alone...

A message is embedded in these payment schemes, and it's coming through loud and clear: To own land is to have the right to degrade it ecologically.

Realizing how sensitive and interconnected our natural lands are, and how long it can take for them to heal once damaged, should give anyone pause when considering how private lands are used, and any time public lands are opened to private interests.

After all, can land which has been here for billions of years and will presumably be here for millions more ever really be "owned" by some mammal with a sub-100-year lifespan? And if not, what justifies our abuse and destruction of it?

Labels: Environment, Politics

07 August 2006

Are we too weak for renewable energy?

Another day, another headline that shows how easily the world's greatest superpower is pushed around by the whims of Big Oil. This time, a breakdown in a BP oil line will slow supply and drive up already record-high gas prices.

Is this really what we want for America? To be dependent on a few major corporations for our welfare, to have our economy and ecology rocked by the slightest mishap in oil production? To be this vulnerable, this exposed to catastrophe at all times? Do we want to be this weak, this unable to provide for ourselves?

What happened to the American spirit of independence? We're a nation of floundering addicts. Now if we put our collective muscle behind natural energy--solar, wind, modern hydroelectric, biomass, etc--we'd make some real progress. We'd have indefinitely renewable energy that's not wasteful, not polluting, and not at risk for the kind of ongoing nonsense we see with oil.

Renewable energy sources are the real way to go for energy independence--they can be scaled from individual homes to nationwide grids, they're not vulnerable to the same kind of large-scale breakdowns and shutdowns as oil. And their development can create potentially millions of jobs here in this country, not in some overseas oil field. And unlike with, say, mountaintop removal coal mining, those energy jobs can come without the cost of ecological and community disaster.

If we could just collectively dig in and commit to real energy independence, we could be a beacon to the world and free ourselves of the economic dependence that muddies our policies in the Middle East and elsewhere. Renewable energy is more reliable, safer, cleaner, more decentralized, and ultimately, more American.

So where is that spirit of independence? When will we finally have the guts to break our habit? Where is the leadership in our government on this issue, and why are we not demanding more of it? I haven't been demanding it enough, but I'll start to--wanna join me?

Labels: Environment

23 July 2006

Who poisoned our water?

I was reading an article in the local Columbia Missourian paper the other day when something struck me.

...boiling doesn’t neutralize chemical pollutants, such as pesticides or weed killers. Don Harter, who leads survival campouts for local Boy Scouts, says chemical pollutants are a problem in Missouri streams because of the large amount of agriculture in the state. The only way to neutralize these chemicals is with water purification tablets, iodine or a carbon filtration device. Generally it’s best to go to spring-fed streams for drinking purposes.

This isn't news, but in the moment it really hit me--our entire stream and river system is poisoned, and no one's being held responsible for it! Companies like Monsanto are pushing enormous quantities of pesticides, and large-scale commercial agriculture is dumping them all over the place, and the result is that our whole natural water supply is literally poisonous to us.

How can such a natural resource be so comprehensively poisoned, corrupted, and no one is held accountable for it?

I wonder if it'd be possible to bring a class-action lawsuit against big chemical and agriculture companies. Surely there'd be some way to identify the types of chemicals in the water, and unless they're completely broken down into their component parts, establish a plausible connection to specific manufacturers. Then we could find out to whom these manufacturers sell most of their chemicals, and tests could be run to see where the most runoff is happening.

Anyone have any thoughts on why such a thing would or wouldn't work? I'm just incensed that industry can get away with things like this and our government is too weak-kneed to even pay attention.

Labels: Environment

21 July 2006

Sequatchie Valley Institute

(See a photo album of our trip to SVI)

After spending a week in the Tennessee hills camping and attending workshops at the Sequatchie Valley Institute, what can I say about it in one journal entry that will do it justice? If I tried to write about every single experience, every nuance of event or personality or eye-opening bit of information, it would take far more time than I have, or space than one would want to see filled with type.

Perhaps I'll revisit specific themes or ideas in future writings, but for now I'll just try to share some overall impressions and favorite memories.

In general, it was a remarkable experience on multiple levels. Firstly, it was remarkable on a purely experiential level--just the simple process of camping out for that long (the longest I've done since spending 9 days in Moab, Utah in '98), under hot & muggy conditions not ideally suited to me. Honestly, that was a challenge to me, and while I found myself adapting to challenges as they came up, it continued to find ways to test me, and rising to those was at times fun, gratifying, and exhausting. I know I'm not that well suited to constant change, but I'm also not testing my limits of flexibility either, so this felt good.

It was also a remarkable experience in terms of people & personalities. The mix of people I encountered there was all over the map. From bright-eyed students to enthusiasm-filled veterans of peace studies & natural building to quietly hardy young men and women working to keep the cooperative going, there was always someone new to be discovered and something new about them to be understood. My naturally judgmental observance was constantly working, trying to suss out and peg people and being surprised in the process.

And it was an interesting process. I found myself at times hitting my own wall of patience and understanding, trying to detach myself from the experience in analyzing it but all the while going through the same tests and catharses as everyone else there. In the end, I saw a great crazy-quilt of humanity, of people damaged and hopeful, directionless and disciplined, laughing and quieted with sadness, all doing what needed to be done, day in and day out, doing the work that would sustain them and each other. In the end, that was the answer, the only observation that held up to honest self-evaluation.

To bring things back down to a less abstract level, here are a few of my favorite memories from the week:

- The quiet, solid dignity with which the farmers at Sequatchie Cove Farm talked about progressive ideas of renewable energy, harmony with the earth, and self-sufficiency

- The brilliantly logical explanation of permaculture, and how working with the earth's natural tendencies, instead of forcing an artificial state upon it, can result in both greater abundance and greater ease

- The way that a series of hand-holding circles revealed a growing comfort in and reliance on each other as the week progressed

- The chillingly brilliant film, The Future of Food, which left me convinced that Monsanto is the most evil corporation in the history of mankind

- The talk by Joel from the CDC which opened my eyes to whole new ways of considering what's good nutrition

- Sandy Hepler's illuminating connecting of dots about what factors have led to Western corporate dominance around the world, and the travesties of justice which have come as a result

But it wasn't all heavy! There were plenty of fun things too:

- Going to sleep feeling hot on most nights, then waking up briefly in the middle of the night feeling deliciously cool

- Spending a week eating many things I'd never tried before, yet never feeling any hunger or stomach upset, and losing weight to boot

- Chocolate! Trying some fabulous South American chocolate (and coming home with two pounds of it)

- Drawing a little design for one of Frances' demonstrations that was quickly adopted as the "logo" for the whole workshop

- Singing under a night sky to a group of strangers who'd become familiar

- Watching a group of toddlers alternately bring joy to and wreak havoc on the scheduled events

- Becoming used to not showering and becoming comfortable in an unlikely setting for me

- Hardly getting any bug bites at all, and no sunburn!

- The enormous amount of natural beauty I was surrounded with every day

But above all the various details of ideas and interactions through the week, there was something which made this experience more special and more fun than anything else, and that was the joy of more deeply connecting with someone I love immensely. This whole thing was conceived in a moment of enthusiastic hope by me and Ann Marie, and it turned out to be a wonderful, I'll say magical, experience in growth, understanding, and devotion for both of us. Through constantly learning more about each other by exposure to these experiences, through transcending challenges to each other to reach states of greater appreciation and gratitude, and through the simple joy of experiencing everything with and through each other, we achieved a profound level of feeling that I'm grateful for and really, really happy about. It's hard to do it justice prosaically. What can I say--I love you, Ann Marie.

So, all in all, a richly satisfying and challenging week of exploration and discovery in the company of a group of searching, striving, mixed-up, wise, and quietly beautiful people, all under the noble watch of the grateful and supportive earth.

Labels: Environment, Life

07 May 2006

In praise of darkness

I was intrigued and delighted by a long, in-depth article in today's Columbia Missourian about...the night sky. Specifically, how our city is considering a light ordinance, and the myriad issues connected to such a thing--free markets vs. regulation, light pollution vs. safety, etc.

What impressed me the most about the story was that it addressed the conventional "vs." positions mentioned above, but moved the discussion right through them into the underlying issues at stake. The result is a situation which could possibly turn out to be pretty simple: use light, but use it wisely.

Different types of outdoor lighting fixtures can have a great impact on the amount of light that's cast to the side and upward, which in most cases is simply wasted light that offers no benefit in terms of safety. In fact, it can have potentially serious detriments: light cast to the side and upward can create glares which actually inhibit properly seeing what's around you, and studies have shown that exposure to artificial light at night can increase the chances of breast cancer in women (it was to do with production of melatonin being inhibited by light).

Hopefully, the result of this proposed ordinance will be something that will help keep our night skies from turning into even more of the pink fuzz that they already are while not putting an excessive burden on businesses (who often claim to want more light for safety, but really just want more visibility for the sake of marketing).

For more background on this concept (including night-sky-friendly lighting fixtures), see the International Dark-Sky Association.

Labels: Environment

A moment at the creek

My first impression of the Hinkson trail, after my first run on it a few weeks back, was that it wasn't as scenic/attractive as my old haunts on the MKT trail, but how much closer it was to me--making runs quicker and easier to schedule, and saving me on gas--made it worthwhile. In the time since, I've changed my tune and have found many small and not-so-small things in which to delight.

After another nice run on Saturday, I felt a compulsion to linger a little longer and wander around a bit. So, after stretching, I walked across the gently rolling hillocks surrounding the trailhead, taking the rocky path down to the creek. With no one else in sight, I felt a pleasing sense of reverence in the aloneness with this untroubled nature. Walking down to the creek's edge, I crouched down and just watched, and listened. What little noise there was from the nearest road was quickly forgotten in the quiet of the moment.

Looking over the gently rushing water (the area I'd walked down to is fairly rocky, providing much surface for whooshing and babbling of the brook), I spotted what looked like a piece of paper wrapped around a rock, plastered against it by the force of the water. Thinking that it probably wasn't doing much harm but was still an interference to anything green growing on the rock's surface, I grabbed the nearest fallen branch-piece, reached out over the water, and set about trying to loose it from its lamination. After several tries, I was finally able to peel it off and lift it out of the water.

That it was so tidily intact should have tipped me off, but I found that it was not paper but instead plastic. Specifically, a plastic bag from a child's birthday party. There are a hundred ways it could have gotten in the stream, but I was just glad that I'd gotten it out. It's simple presence as a foreign pollutant is clear to anyone, but lately I've been reminded of how dangerous plastics can be to the ecosystem through reading articles like the recent ocean study in Mother Jones magazine.

After pulling it ashore and setting it down next to me, I returned to my meditation over the gently rippling water-sounds. Then I noticed, just a couple yards upstream, a small bird alight on a low branch overhanging the stream. (I think it was an Eastern Phoebe, but it may have been an Eastern Kingbird; my bird IDing skills are woefully poor.)

Keeping quiet and still, I was treated to a delightful show by the little one; a series of looping dips down into the water, then swooping back up to the branch to wash itself and shake itself dry. Mixed into this cleaning ritual were a few cursory above-water swoops, presumably to snag the occasional insect. I waited long enough for the bird to finish and move a little further downstream before getting up and walking back up to the car.

Another reminder that most of my fondest memories, those that stay with me and emerge in the most thoughtful and meaningful times, don't involve concrete.

(This journal entry typed to the accompaniment of Bert Jansch's lovely and pastoral 1980 album, Avocet.)

Labels: Environment, Life, Running

29 April 2006

Ode to Hinkson

Quiet

Soft damp bed of green

Soaking up step-sounds

Mushed dust of old mountains

Crackles gently underfoot

Deep rusted red herald

A hoary halo overlooks comers, goers

In the soaked gray air it's deepened

I give a salute of auburn curls, underby

Alone and surrounded

Echoing, chirping, rustling life abounds

Slithers, flutters, hops, buzzes, whispers

In a language too slow for me to catch

A lightness fills me

Stands me up, lifts me along

As my legs stretch around solitary bends

And a fleeting connectedness washes through

The curves create friction

The inclines spark surges

The resistance replied with a sweaty push

Hot breath and hammer-heart

Soft-tails alight

Retreating to their canopy

Human ruin a muted presence at the fringe

All come and go in the closest thing to peace.

Labels: Environment, Poems, Running

01 April 2006

Act Now! Save Missouri forests

The President's FY07 budget includes a proposal to sell hundreds of thousands of acres of national forest land to help make up for a shortfall in rural school funding due to declining timber sales. The money to be raised is a tiny fraction of the money we're pouring into the debacle in Iraq (it's equal to roughly 3 days' worth of warmaking), and could easily be found in other ways. This would affect dozens of states, and Missouri would be one of those most affected, with more than 21,000 acres on the chopping black.

For those already familiar with the proposed sale, you can easily send an editable form letter to the Forest Service, courtesy of the Wilderness Society, or if you want to do it on your own, you can e-mail comments directly to SRS_Land_Sales@fs.fed.us. The deadline for public comment is May 1, 2006, so act now!

Now, for those who may not know the details of the issue, here are a few resources with which to get up to speed:

- Missouri congressional delegation takes stand against Forest Service plan: Kudos to Sens. Kit Bond and Jim Talent, and Reps. Kenny Hulshof, Jo Ann Emerson and Roy Blunt for seeing this turkey of a plan for what it is.

- Details of the proposed plan: Fact sheet, list by state and region of how much land would be sold, and related stories.

- Forest Service looking beyond timber sales for revenues: The Forest Service has other lousy plans in the works for further commercializing and opening up our national forests to development.

- Senators propose alternative to forest sale: Two western senators present a plan that would generate several times more money than the proposed sales--simply by closing a tax loophole on deadbeat government contractors.

- Forest Service wasting taxpayers' money: Far from being a responsible steward of our shared resources, the Forest Service is making a disastrous mess of things that is costing us all billions of dollars. Read this to help shed light on why the timber program is a failure.

Labels: Environment, Politics

28 December 2005

Biofuels: The unfortunate dark side

I wanted to believe in it, I really did. I saw the smiling hippie faces driving down the road in converted old Volvos, Mercedes, Subarus, and the promise--fuel from simple, harmless vegetable oil?--seemed almost too good to be true, yet there was the proof, driving down the road. And it's true--good old fashioned vegetable oils and fats can be converted to perfectly usable fuel.

What I didn't realize, and am now starting to realize, is that the question isn't whether biofuel technology works or not, but rather its implications.

In short, it looks like the biofuel option would be an environmental disaster.

The reasons have primarily to do with a combination of where biofuels come from and the scale at which they'd have to be produced. The commercial production of biofuels is very environmentally destructive, and the amounts needed would ensure mammoth devastation of natural forests and habitats, likely hastening the extinctions of some of our most endangered species--orangutans, tigers, rhinos, gibbons, and more.

So those smiling hippies have the right idea, but as is so often the case, our monstrous population growth and ever-increasing transportation demands obliterate the practical application of something as seemingly benign as biofuels. Biodiesel, soy, you name it--the scale at which we consume is rapidly leaving us with no responsible choices left at the societal level. Once again, we find ourselves painted into a corner where the only option is to consume less. A lot less. For now, we have a choice, but it's only a matter of time before we don't.

A few generations from now, what will our children think of this era in which thoughtless luxury and a selfish focus on personal freedom at all costs left them with a long list of extinct animals and a crisis of energy and natural resources?

For more information on this topic, read this excellent column by the always-insightful George Monbiot. See also this brief overview of the situation.

Labels: Environment

20 November 2005

More on land use: The dispossessed

The reliably intriguing Orion magazine's current cover story is a fascinating look at the real losers in the battle between conservation and development: indigenous people. It's well worth your time to read.

This story exposes a sad byproduct of the ongoing effort to protect the natural world from abuse and overdevelopment. So much of the world's natural resources are being consumed and destroyed at unsustainable rates and in woefully irresponsible ways, and the result is two camps which take extreme positions on the issue. The consuming corporations, driving themselves on a mad path into unsustainable growth for the sake of unlimited profit, demand unlimited access to and use of natural resources. Environmental groups, seeing the truly natural & untainted parts of our world diminishing rapidly, are compelled to take an equally strong and often absolutist stance at the opposite end of the spectrum, just to slow the devastation.

But no human interaction with the world exists in a vacuum, and whether it's the pollution and habitat destruction of commercial development or the cultural and economic limitations imposed by conservation, there is always an effect when we seek to manipulate the way of things. Though I favor the environmentalist side of the debate in virtually all cases, issues like these highlight the need for an overarching look at how we can better relate to the land as something we're all connected to--something we all have a right to interact with and use, but which we don't have a right to destroy or abuse.

Labels: Environment

19 November 2005

What does it mean to use the land?

Firstly, I must mention that this post is inspired by a very serious issue that should demand our attention: a mining-law revamp that was slipped into the House budget bill by two Republican representatives. I urge everyone to learn more about this issue and to contact your local senators to encourage them to oppose adoption of this proposal (and to contact your local representatives to let them know you don't approve of this type of behavior).

Says Amanda Griscom Little in the above-linked story from Grist magazine:

It would allow the Interior Department to sell tens of millions of acres of public lands in the American West -- including more than 2 million acres inside or within a few miles of national parks, wildlife refuges, and wilderness areas -- to international mining companies, oil and gas prospectors, real-estate developers, and, well, anyone else who's interested ... [the proposal] would not require buyers to prove that mineral resources exist beneath the property they want to purchase, nor that they use the land for mining ... And since the land would be privately owned and no longer under federal jurisdiction, it would be immune to environmental reviews ... or public input on development plans.

Though the measure's sponsor isn't publicly commenting about it, the measure's stated goal of economic help and deficit reduction is thin at best and the cost--the potentially irreversibly destructive use of our public lands--isn't worth it.

Thinking about this issue, I've pondered the more general concept of what it means to 'use the land'. Notions of 'the land providing for us' and the Biblical references to man having dominion over the wild things are pervasive underpinnings for our American views on land use, but things like this mining measure, to my mind, put a perverse twist on such hallowed ideas.

To me, 'using the land' is a two-way relationship, where the land's natural resources give us food, shelter, and energy, and we in turn care for the health of the land both to sustain its productivity and out of simple respect for its inherent value. But more and more we see commercial development that uses land for little more than a horizontal surface which can be paved over and stacked with generic, wasteful, polluting attractions which stand apart from their surroundings in every sense (physical, visual/aesthetic, spiritual). I believe there must be a tipping point at which we have to take legal and legislative measures to enforce the boundaries of a respectful relationship with the natural world.

If you agree, please contact your congressional representatives and let them know how you feel. (For those interested in thinking more about the issue of relating to the land, I recommend reading the works of Wendell Berry, the most insightful curmudgeon I've yet seen on these issues.)

Perhaps the question, at the end of the day, can be put this way: is the world something we take from, or live in?

Labels: Environment

12 November 2005

Quick environmental primers

Being a recognized green-type by people I know, I'm often called on to give explanations for my environmental positions or to answer questions about effective choices (that's a nice way of saying that people sometimes try to stump or challenge me). Since talk of sustainable, ecologically responsible living can easily get preachy (and because I'm a far-from-perfect sort who can use reminders about the best things to spend or not spend energy and worry on), here are a few delightfully quick and informative guides from Grist magazine to help anyone make good environmental choices in their own daily lives.

- A Consumption Manifesto: How to streamline your life and still enjoy the heck out of it

- The most common questions & answers about making eco-responsible choices

- A day in the life: responsible choices from waking through the end of the day

Labels: Environment

22 June 2005

Wal-Mart's green swindle

Call me a slow thinker, but there was something about Wal-Mart's "green space trade" plan, announced a couple months back, that bothered me from the start but which has only now crystallized. The company's plan is to buy and preserve an amount of land equal to that which it develops for its stores over the next ten years, to in effect compensate for its development with non-development elsewhere.

What bothers me most about it is the logic that underlies such a deal. I think of it as a sort of "kindly thief" offering: a thief who tells you that he's going to rob as many houses as he likes for as long as he likes, but he promises to avoid robbing one house for every house he robs. Doesn't sound like much of a deal, does it? But the logic is essentially the same. This "gift" we're getting from Wal-Mart is something we already have: undeveloped land. What's implied in this deal is that the un-bought, un-developed land out there now is theirs, not ours. It's theirs for the taking, and the fact that they're going to buy it for us makes us little more than hapless bystanders watching the company wield its power. This supposed altruism is little more than a chilling demonstration of how much power this company has.

Some might take my attitude as sour grapes--does this liberal have to badmouth everything? But Wal-Mart is profoundly exasperating to me. What they do is permeated by awful, avaricious policies: anti-union, anti-women, environmentally unsound (through vast clear-cutting developments, runoff pollution, noise/light/traffic pollution, etc.), contributing to massive trade deficits, placing huge tax burdens on local communities...it goes on and on. What's exasperating, though, is that they don't have to do any of this.

Wal-Mart is an enormously profitable company--some would say obscenely profitable. They could allow employee organizing, develop their store sites in community-friendly ways, sell more domestically-made goods, pay decent wages and benefits to their employees, and still make a healthy profit. But like Enron, they seem more concerned with maximizing profit at any cost and expanding scale at an unsustainable rate. Wal-Mart could settle down and become a model of ecological and pro-labor practices--they have the money and clout to do it. But instead they continue to barrel ahead ravenously, and the scale to which they're building their operation will, also like Enron, force them into more and more hurtful business models just to keep them afloat.

Consider one green Wal-Mart development on the drawing board in Vancouver. Take a look at that, and then think about how the Wal-Mart(s) look in your town. Wouldn't this design be vastly better for you and your town? Why isn't this the norm? Why do we let them get away with the mediocrity they offer us? Are cheap (and cheaply made) goods really worth what they do to our local businesses, our streams, our souls?

At the end of the day, there's only one kind of green that Wal-Mart cares about, and that's the green of filthy lucre.

Labels: Environment

27 April 2005

Oil, consumption, and eco-technology

First off, I was all set to write a rant on our country's cozy relationship with long-time human rights-abuser Saudi Arabia when I discovered that Amitabh Pal from The Progressive had already posted an elegantly powerful summary of the dangerous nature of this connection. It's definitely worth reading, as it points out a major inconsistency in how we deal with the issues of freedom and democracy abroad, and how our ravenous desire for oil is helping to build an economic and cultural powerhouse overseas which is in many ways opposed to our ideals.

In another bit of synchronicity today, I found myself pondering issues of energy and resource consumption only to find a few intriguing readings on that topic which share a focus on an idea we hear far too little about: conservation, or the reduction of consumption. It's easy to get lost in the idea that the most crucial issue for us is the type of energy we're using. I often find myself focusing on the damaging nature of oil, coal, and nuclear energy production and use, and longing for exploration of cleaner technology like wind, solar, and hydroelectric. But as important as those issues are (and they're incredibly important), what often gets left out of the equation is the variable of our ever-growing demand for energy, and how this essentially damns us in the end no matter what energy source we choose.

A thoughtful article by Bill McKibben in the latest issue of Orion magazine looks at the pressures and motivations that push us unthinkingly past consideration of "how can we use less?" to a knee-jerk response of "how can we get more?" McKibben notes our instinctive behavior of focusing on the most immediate problem, our patterns of solving one day's problems and then moving on to the next day's, and how it's more difficult to sustain focus on something long-term. Reliable analysis indicates that world petroleum production has just about peaked, while consumption is accelerating rapidly. Solutions designed only to reduce costs or increase availability of energy are not enough--they're just short-term band-aids for a larger problem.

That thread was picked up this week by author and Guardian columnist George Monbiot in a thoughtful column about the fallacy of focusing too much on technology as a solution to energy issues. He focuses on wind farms, but really makes a larger point about how we're going about the energy debate:

Alternative technology permits us to imagine that we can build our way out of trouble. By responding to one form of over-development with another, we can, we believe, continue to expand our total energy demands without destroying the planetary systems required to sustain human life.

...What is acceptable to the market, and therefore to the government, is an enhanced set of opportunities for capital, in the form of new kinds of energy generation. What is not acceptable is a reduced set of opportunities for capital, in the form of a massively curtailed total energy production. It is not their fault, but however clearly the green groups articulate their priorities, what the government hears is "more windfarms", rather than "fewer flights".

Finally, a long and thorough (but very worthwhile) piece by Norman Church delves into how our food supply is dependent on oil, how the incredible inefficiency and wastefulness of food production, packaging and transportation places a great variety of burdens on our environment and energy resources. This dependence and inefficiency make the food supply vulnerable and unsustainable.

The answers to these issues can't be fit easily into a few words, but it's exciting to see what seems to be an increasing focus on the core issues of interconnectedness and interdependence, and how only a comprehensive view of the entire system--biological, economic, social, technological--can really address the problem.

But in the meantime, a good guideline for us to follow is to simply minimize the amount of energy consumption that goes into what and how we buy. That idea can be deceptive; it doesn't mean to save a bit of gas by driving to the nearest Wal-Mart and buying everything in one place. The seeming economy of such a choice ignores the massive energy use and inefficiency of running such an enterprise (not to mention the vast array of immoral corporate practices at Wal-Mart, which is a topic for another day). No, in this case we're better off going down to the local farmer's market. It may be a little less convenient in location or schedule, but the closer you get to the direct source of anything, the less wasteful the process becomes. The spinach and bread Ann Marie and I bought at the Columbia Farmer's Market last week wasn't mass-produced on an enormous corporate farm a thousand miles away, using massive quantities of agrochemicals, shipped on enormous boats and tractor-trailers, wrapped in tons of plastic and cardboard. It was made nearby, using sustainable practices, placed into a car or truck by hand, and driven a few miles to be sold directly to friends and neighbors. And oh man, was it delicious, too.

When I go somewhere like that, I can't help but feel that the solution to many of our problems is so near, so very much within our reach. To paraphrase the old cliché, care globally and buy locally.

Labels: Environment

25 April 2005

Earth Day 2005

This Sunday was the Earth Day celebration in Columbia. It's always a bit of a renewing occasion; I don't get much from the aimless hippies or fire-jugglers, but I am encouraged and reassured by the sight of all the people who are doing the hard work every day to help make the world a better and more responsible place. A recent jibe I heard directed at the concept of Earth Day--"why celebrate the creation instead of the creator?"--made me think, but it ultimately misses the point. Earth Day isn't defined as spiritual or non-spiritual, as religious or pagan. It's an open-ended concept that allows all manner of connectedness to and celebration of the natural world, and our place in it and interaction with it. After all, to respond to the potential religious complaint, right off the bat in the book of Genesis, you have God at each stage of creation proclaiming that it was good, and blessing it. Why would such a statement be included if it wasn't meaningful? And if it is significant, then surely taking a day to echo that sentiment is valid. So take Earth Day as you will, but ultimately I see it as a sign of respect--a sign that many among us still believe that the natural world is something to be cared for, respected, and honored instead of exploited, abused, and pushed aside by suburban sterility.

I've posted a couple photos from the event. Highlights of the day included crowd-pleasing performances by the DragonFlies dance troupe and Hilary Scott.

Labels: Environment

29 April 2004

Judicial science

Songs of the day: Sonic Youth - "Unmade Bed"; King Crimson - "Three of a Perfect Pair"; Public Enemy - "She Watch Channel Zero".

Another day, another transmission from the George W. Bush Bizarro World. Today brings two examples of such intense lunacy, distinguishing themselves from the daily madness, that I can't help but mention them.

First, the latest developments in Fallujah. We'll set aside for the moment that on a day when 10 US soldiers died, Paul Wolfowitz is saying "we've had some success." We'll ignore the continued statements about supposed cease-fires when hundreds of Iraqis have been killed and each day brings new clashes. We'll not discuss that almost a year after Bush declared an end to major combat operations, our troops are in the middle of one of the biggest yet--and have been stopped in their tracks by fierce Iraqi resistance. Instead of those pesky details, let's focus on something I find most disturbing of all: that part of our government's attempted solution to this bloody standoff is to send in an Iraqi army--I hope you're sitting down--that is led by a former general from Saddam's military. Yes, that's right. A former general from the army of the tyrant whose country we invaded is now going to help us put down resistance. Which is...yes, that's right, probably exactly what he was doing before we invaded. This, I think, will certainly reassure the people of Iraq that we have their best interests at heart. Sure, we've slaughtered ten thousand of their civilians, but at least Saddam is gone...oh, except his generals are running our new "protective" army, and members of his party are being let back in to our government. Ah yes, this is much better. (By the way, one laughable "improvement" in Iraq I've heard attributed to our crusade there is that women now have access to education. News flash: Iraq, long ruled by a secular government, has long provided much more access for women than other middle-eastern countries. That is, until changes sparked by our first invasion of the place in 1991 started a major backslide. See http://www.hrw.org/backgrounder/wrd/iraq-women.htm.)

Read more at http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/4824213/.

But international diplomacy has never been Bush's forte, so let's visit another area his government is excelling in--environmental science. It seems that the Bush administration has decided to include hatchery-bred salmon in counts determining the endangered status of wild salmon. Once again, let's set aside minor quibbles--such as the logic of this decision being analogous to counting zoo animals in studies of how endangered apes or pandas are--and focus on the most notably insane qualities of this decision. The Bush administration consulted six scientists, among the world's foremost experts on salmon ecology, but subsequently told the scientists that their conclusions were "inappropriate for official government reports". What apparently clinched the decision for our anti-intellectual administration was--wait for it--the opinion of a U.S. district judge. Judge Michael R. Hogan ruled that the federal government was making a mistake in not counting genetically similar hatchery-produced fish in overall wild population counts. According to Bob Lohn, chief of federal salmon recovery in the Northwest, "there was an inescapable reasoning to Judge Hogan's ruling". Apparently a much stronger reasoning than the considered scientific opinion of the world's foremost experts on salmon ecology.

Read about it at http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/4856765/.

Labels: Environment