04 September 2005

Music without borders

As I mentioned in an earlier post, I've been listening to essentially nothing but King Crimson for weeks now, progressing slowly through their 1973-74 lineup and skipping randomly to earlier and later works (well, I've mixed in a few other things--a pinch of Curtis Mayfield, a little Sigur Ros, a bit of Stars). As I've been enjoying it I've also been picking through it intellectually, pondering its complexity and the way it strains against formula, and also thinking about why it's appealing so much to me now.

The other day I made a connection that helped shed some light on that. I remembered a gig with local flamenco band Los Desterrados I sat in on a couple months ago, a loose session which contained one of my favorite musical-performance moments in ages. In thinking on it, I realized that this performance held a sort of key that has been subtly unlocking me ever since.

What happened at this particular show was an unplanned and serendipitous combination of musicians, a non-group which immediately transcended any genre. In addition to the core guitar and percussion flamenco-based elements of Los Desterrados, there was a cellist and a young woman playing the Cuban tres, an instrument that hovers between a guitar and mandolin. After a few somewhat discombobulated flamenco-esque numbers, the cellist took charge (bless her heart) and launched into something that was utterly un-flamenco, something that was vaguely neo-classical but with a modern rhythmic pulse. This immediately set all the flamenco players on their ears; there was a general sense of having nowhere to hang their hats, musically speaking. Their rules no longer applied, their comfort zones were gone.

By force of numbers alone, they might have overruled her. But, ditching them like a musical double agent, I leapt into the fray with the enthusiasm of a freed prisoner and drove things in her direction, using the weight of the bass to set the tone and to fend off any attempts at conventionalizing the sounds that were, at that moment, swirling out unrestrained by routine, pattern, or unconscious habit. Safely cut off from safe harbour, the musicians were forced to sink or swim, to be fully conscious and present in the moment, and the result produced an energy among us that was entirely unlike what is generated in a typical by-the-numbers genre-specific performance.

As the improvised piece rolled on and billowed, the energy grew; I found myself grinning like a fool as I acknowledged its presence, opened myself to it, and felt it connect me to everyone else there. In that moment we were conduits; we were playing things we never played, working together in ways we never worked together, becoming enveloped in a flow and electricity which came from no plan or intention. I wasn't trying, I wasn't working; I was just keeping up with this essential sound coming from within and without me, through my hands. It was a form of ecstacy. A few times I looked up into the faces in the audience, and saw glimpses of hushed wonder there; they too were feeling it and in their quieted near-reverence were participating in it. I could tell that while some were distracted, others were truly "getting" it.

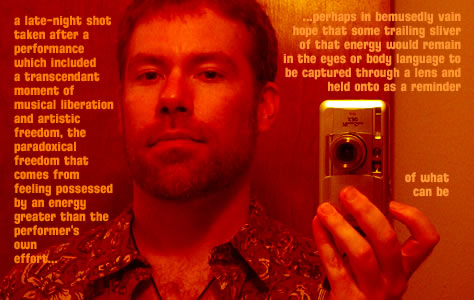

The same held true for the musicians. As the energy of the piece gradually trailed off and evaporated into a gentle, equally unplanned finale, there were looks on our faces ranging from flushed to intense to bemused bewilderment. A few seemed to realize what had happened; others were confused; some were simply pleased and surprised. But I knew what I'd felt, what I'd experienced--an extended moment of freedom, of artistic levitation, of no rules, no borders. At that moment I wanted more of that. I didn't want to play anything rote, anything easy and familiar. I wanted to go chasing off after that energy, that muse that exists wholly above the level of a predictable band having a good or even great night.

With that in my blood, it's little wonder that I've since found my way to immersing myself in music that pushes barriers right down and walks in places alternately shadowy and brilliant; places whose darkness is the kind of deep, damp dark that only comes from digging very hard and deeply; whose light is the crisp sun that warms a peak found by struggling up a twisting, rocky path. Like anything else, music is full of routine and drudgery and frustration; but in my experience of it, it's the one thing that holds the potential for the type of transcendence that can make months of slogging, and an entire confused and yearning life, seem worth it to me, many times over.

Labels: Music